This trip to Panama has been a little different than normal – we have a group predominantly composed of invertebrate paleontologists and paleobotanists, but have few vertebrate paleontologists. Where do you go in Panama if you want to find invertebrate fossils? Well, you can’t go wrong with the Gatún Formation, which has enchanted malacologists (mollusc-workers) for over a century.

Panoramic photo of the San Judas locality, near the town of Sabanitas in Panama. Photo by C. Robins.

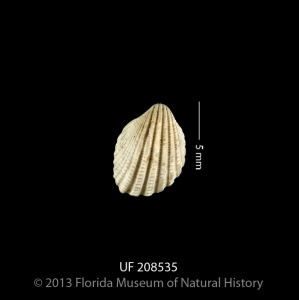

We headed to Gatún on Thursday. It was an incredibly muddy day, with thunder often rumbling in the background, but we were lucky to have a wonderful collecting day. We ended up with over 1,000 invertebrate fossils; mostly molluscs, but with a few decapods, too.

Post doc Adiël Klompmaker keeps his paleo-paper easily accessible for fossil-wrapping. Photo by C. Robins.

Turritellid gastropods dominate some areas of the Gatún.

We tried out multiple localities within the Sabanitas area, but found many had become overgrown and inaccessible in the last few years. This is a constant issue in Panama, where the erosion rate is high and the plants are constantly reclaiming the open space.

We have Prof. Jon Hendricks with us on this trip. He is a specialist in cone shells, and has been working on their phylogeny. He uses UV light to see their color patterns, which have long-since vanished from our visible color palette. We managed to collect around 500 cone snails for him, which was about half of the day’s total haul! (That’s not a true representative of Gatún diversity.)

Dr. Jon Hendricks sorting his fossil cones after a long day in the field.

After a productive day in Gatún, today we stayed in the canal zone. We were able to access the Empire Locality, a locality full of decapods that had previously been within the construction zone, and thus inaccessible to collecting.

Collecting in the Panama Canal – the crabs are too good to pay attention to the scenery!

Roger Portell and Adiël Klompmaker hunt for decapods alongside the Panama Canal.

An anteater even tried to help us find fossils. He quickly headed back into the vegetation. Photo by Adiël Klompmaker.

Friday proved to be an incredibly hot day, and we almost welcomed the torrential downpour that arrived around 1PM. The excessive lightning, however, forced us in for an early end. Tomorrow (Saturday) is our final field day, which we will spend as a divided group – part of the group will hunt for crabs, and the museum interns will finally get a chance to test their vertebrate paleontology skills at a few canal sites!