Culebra Cut

A few weeks ago, when we were driving to one of our dig sites, we noticed a dip in the road that hadn’t been there the previous week. When we returned to the site the next week the dip was lower by at least six inches. The following week I decided driving down that road was not in our best interest but we wanted to investigate. We were able to document cracks and fissures that were several feet long and 4-12 inches wide. The next week there were men surveying the area and the week after that there were excavators and backhoes. I had read about the massive landslides during the construction of the canal and was aware that due to the geology of the area they are an ongoing problem. It was fascinating and I have to admit a bit disconcerting to watch the progression of the landslide and the remedial measures that were taken in response. I was so intrigued I did a little bit of research.

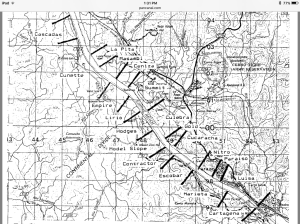

Landslides have always been a problem in the Panama Canal, most notably in the 13-km long section at the southern end of the canal known as the Culebra Cut (also known as Gaillard Cut). The special wonder of the canal is Culebra Cut. It cuts through the continental divide and is the high, hard rock basaltic slopes and the lower, soft shale/clay slopes of the Cucaracha and Culebra Formations that can be seen in picturesque photos of the canal. All the rain and humidity softens the shale into mud and clay. The instability of the mud and clay results in continual landslides. David McCullough in “Path Between The Seas”, his famous book about the building of the Panama Canal, states that all technical problems were small compared to the slides in the cut. Workers on the canal would arrive in the morning and months of digging, as well as equipment, would be completely wiped out by thousands of cubic yards of dirt and rock from slides. The massive slides in the cut also played a big part in the French Canal Company’s inability to complete the canal.

In 1915 the second year of operation, the canal was hit with two major landslides that struck simultaneously. Both the east side and west side of the Culebra Formation slid, resulting in the closure of the canal for seven months. In 1986 a geotechnical advisory board was formed after a major reactivation of the East Cucaracha slide encroached into the navigational channel of the canal and caused a closure of twelve hours.

In 1988 a report was issued by Luis D. Alfaro on the risk of landslides in Gaillard Cut. He researched all of the slide events that were documented up to 1986, thirty-one in all. In his report he suggests dividing the cut into zones of relative uniform geological environments to help monitor and document movement. We use these zone names at our dig sites. Today the slopes are monitored constantly through instrumentation and field inspections so remedial measures can be implemented if movement is detected.

Culebra Cut

The good news for us is that there is now a newly scraped-clean excavation site for us to investigate for fossils. We went there twice last week and discovered shark teeth, croc teeth, and a bunch of invertebrate fossils.